Twenty-five years ago, watchmaker Michel Parmigiani, with the support of the Sandoz Family Foundation, founded Parmigiani Fleurier. The company has grown considerably since then and the brand, as well as its related companies (which include movement manufacturer Manufacture Vaucher, casemaker Les Artisans Boitiers, and others), have become well-established features of the Swiss watchmaking landscape. In celebration of the company's anniversary, Michel Parmigiani and a team of artisans and designers have created something extraordinary. I haven't seen the watch in person – it was finished very recently and the entire project, from conception to completion, took less than a year, which is incredible for such an elaborate piece. So I'm a little shy of saying it's the most beautiful watch I've ever seen. It's up there, though, based on the images – and whether by happy accident, deliberate planning, or a fortunate combination of Michel Parmigiani's personal obsessions, the history of watchmaking, and (work with me here) the history of mathematics, what came out of the whole process was a three dimensional, kinetic, visual, and aural expression of something rooted deeply in nature.

There is a lot to unpack, and I mean a lot. The impetus for this particular project came from Guido Terreni, who for many years headed up the watchmaking division of Bulgari and who left last year to become the CEO of Parmigiani Fleurier. One of his first objectives was to introduce a new collection that would serve as both a breath of fresh air and also a sort of manifesto for the direction in which he hopes to lead the company. The Tonda PF collection feels like a real shot in the arm for the company – I finally had a chance to see the collection in person just last week – and La Rose Carrée, miraculously enough, feels both on the same continuum as the Tonda PF collection, while at the same time being something on an entirely different level.

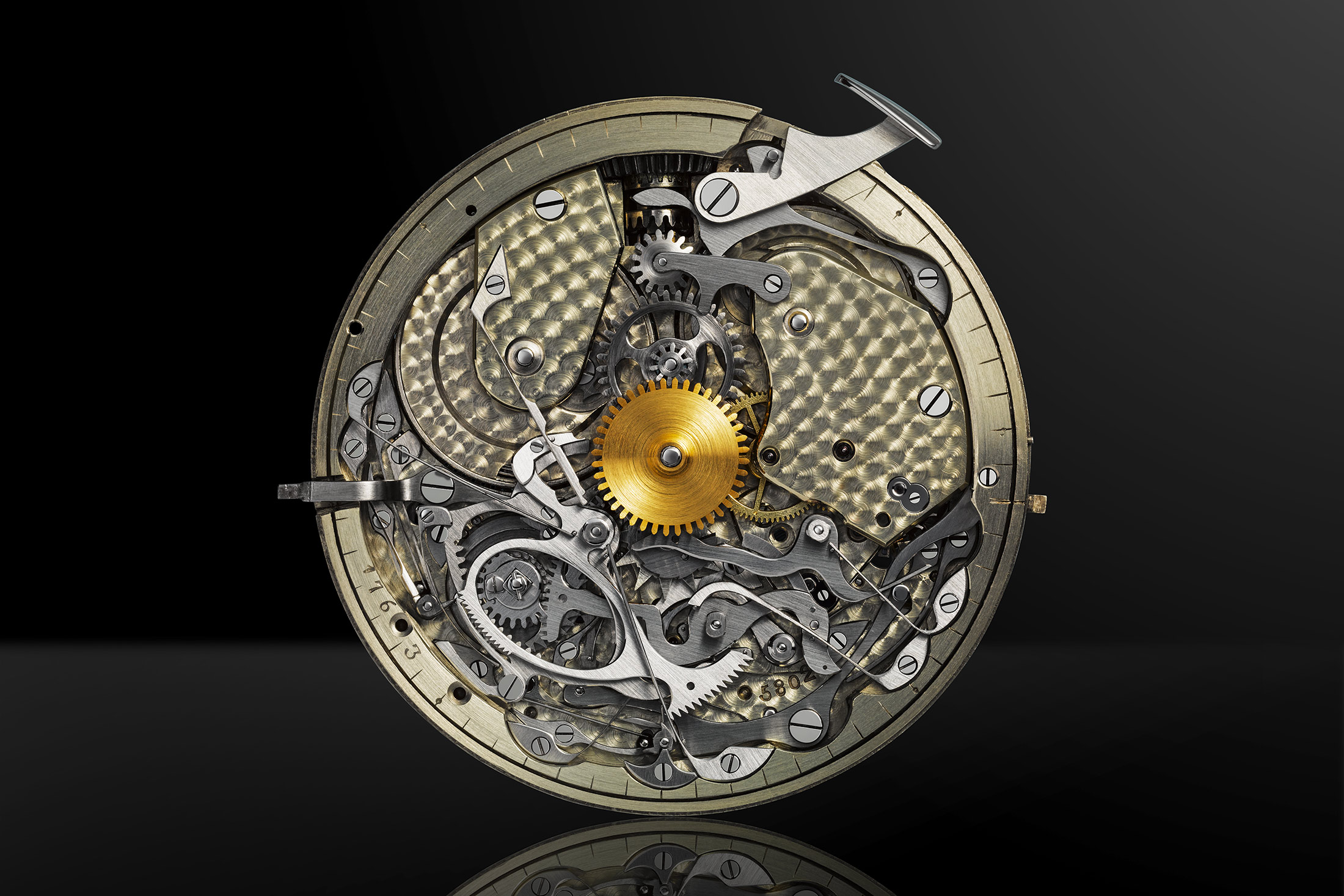

The watch is a large, 64mm x 20mm grande et petite sonnerie and minute repeater, with a movement made by Louis-Elisée Piguet, number 5802. The movement, according to Parmigiani Fleurier, was completed sometime between 1898 and 1904, but never cased. Eventually, it became part of the assets of the restoration workshop at Parmigiani Fleurier and for the 25th anniversary, Michel Parmigiani and Guido Terreni decided to use it as the basis for a highly decorated pocket watch.

The movement was not a complete blank, but it was necessary to give it a level of decorative finish appropriate to the quality of the movement and the ambitions of the project. The team working on the watch briefly considered applying a traditional finish of Geneva stripes but as the movement had already been assembled and largely finalized in its finish by Louis-Elisée Piguet, this wasn't possible as Geneva stripes would have altered the tolerances of the bridges. Instead, decorative engraving was applied in keeping with the overall design scheme of the watch.

Anne-Marie Moser, designer.

A Golden Spiral; source, Wikipedia

The design for the watch obviously had to be established before any actual work could be undertaken, and the design was finalized by Anne-Marie Moser, who also executed the drawings that would guide the creation of the watch. Michel Parmigiani's own work has often been characterized by a fascination with the Golden Ratio. The Golden Ratio is a simple mathematic ratio: take a line, and divide it into two segments. If the ratio of the longer segment to the smaller segment is the same as the ratio of the longer segment to the entire line, then the ratio is the Golden Ratio – an irrational number, like the square root of two (to pick just one example). The Golden Ratio is equal to: 1.61803398875 ... and on into infinity.

Irrational numbers were known to the ancient Greeks but they drove them nuts, because they were, well, irrational – that is, you can't express the ratio as a ratio of two integers. The Greeks, for whom mathematics was, fundamentally, geometry, took the irrationality of irrational numbers very personally – they were nothing less than an affront to the notion of well-ordered numbers as the basis for a well-ordered universe. Supposedly, they were discovered by a disciple of Pythagoras, named Hippasus, and the discovery was so upsetting that, depending on who you read, he either got thrown overboard from the ship he and his comrades were traveling in or was exiled.

The interior of the shell of the chambered nautilus. Image, Wikipedia

The Golden Ratio is closely related to another fundamental mathematical discovery – the Fibonacci Sequence. To generate the Fibonacci numbers, you start at zero and then start adding each number to the preceding number: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, and so on, ad infinitum. The Fibonacci numbers were discovered by the 13th-century mathematician, Leonardo Bonacci, called Fibonacci (filius Bonacci, or "son of Bonacci") who was able to do so thanks to his exposure to early forms of Arabic numerals, during his travels around the Mediterranean as a young man, during which time he met Arab merchants and mathematicians who showed him the number system. The ratio of any given Fibonacci number to the preceding number approaches the Golden Ratio more and more closely as the numbers go up, and if you take the limit at infinity, the two are equal. You can generate a Golden Spiral by taking a square, increasing the length of each side by the Golden Ratio, and nesting them inside each other and it's this spiral that is the most often found expression of the Golden Ratio in nature. (The Golden Spiral is a special case of the logarithmic spiral).

The Golden Spiral was the basis for the "rose carrée" decorative motif found throughout the watch. The movement decoration uses the same motif found on the covers, and on the bezel. The movement beveling, which preceded the engraving, was done by Bernard Muller.

Movement beveling, by Bernard Muller.

The goal was to respect the heritage and history represented by the movement – at the time it was made there were very, very few craftsmen working in Switzerland capable of making such a caliber – while at the same time, giving it an aesthetic that was harmonious with the rest of the watch.

Engraving of the rose carrée motif on both the movement bridges and on the case was carried out by engraver Eddy Jaquet. The movement's final appearance is the result of both the traditional finishing carried out by Muller, and the project-specific engraving done by Jaquet.

The striking works, on the dial side of the movement.

The back (top plate) of the movement. The balance is at the lower left, with the hammers at 3:00 and 5:00. The two barrels at the top are for driving the striking works (left) and the going train (right).

The creation of the case was equally challenging although in a different way. The same rose carrée motif used on the movement was used on the case, as well. The work is extremely detailed, and because the entire design of the watch is based on the expression of very rigorously defined mathematical and geometric relationships, there wasn't much of a margin for error at all, as any irregularity would have been immediately visible.

Engraver Eddy Jaquet

Enameling was carried out by Vanessa Lecci. There isn't really any room for mistakes in any of the work necessary to create this kind of watch, but given the number of things that can go wrong during the enameling process, I have always thought that enamelists must approach their work with a certain level of feeling. Most of the ones I've had a chance to meet in person have been cordial but you get the feeling that they'd really rather not be talking to journalists – in fact, sometimes I feel as if they'd rather not be talking to anyone at all. The case for La Rose Carrée is enameled in a deep blue intended to be reminiscent of the color of "a body of water as seen from the sky," says Michel Parmigiani and you can't help but think of how the Mediterranean Sea might have looked, on a clear afternoon with good weather and fair winds, to an intrepid young would-be mathematician named Leonardo Bonacci.

Enamelist Vanessa Lecci at work.

Enamel starts out as crystals of glass, which are ground to a fine powder by the enamelist, by hand. You judge whether or not you've got the right texture by feel, eye, and ear; the powder makes a particular sound under the mortar and pestle when it's the right consistency.

The liquid enamel is then applied to the metal substrate, and fired. The process of creating the covers for La Rose Carrée was made more difficult by the depth of the engraving and the size of the dial. The challenge was even greater because Lecci had to pull off the enameling not once, but twice – both covers of the watch are engraved and they are mirror images of each other.

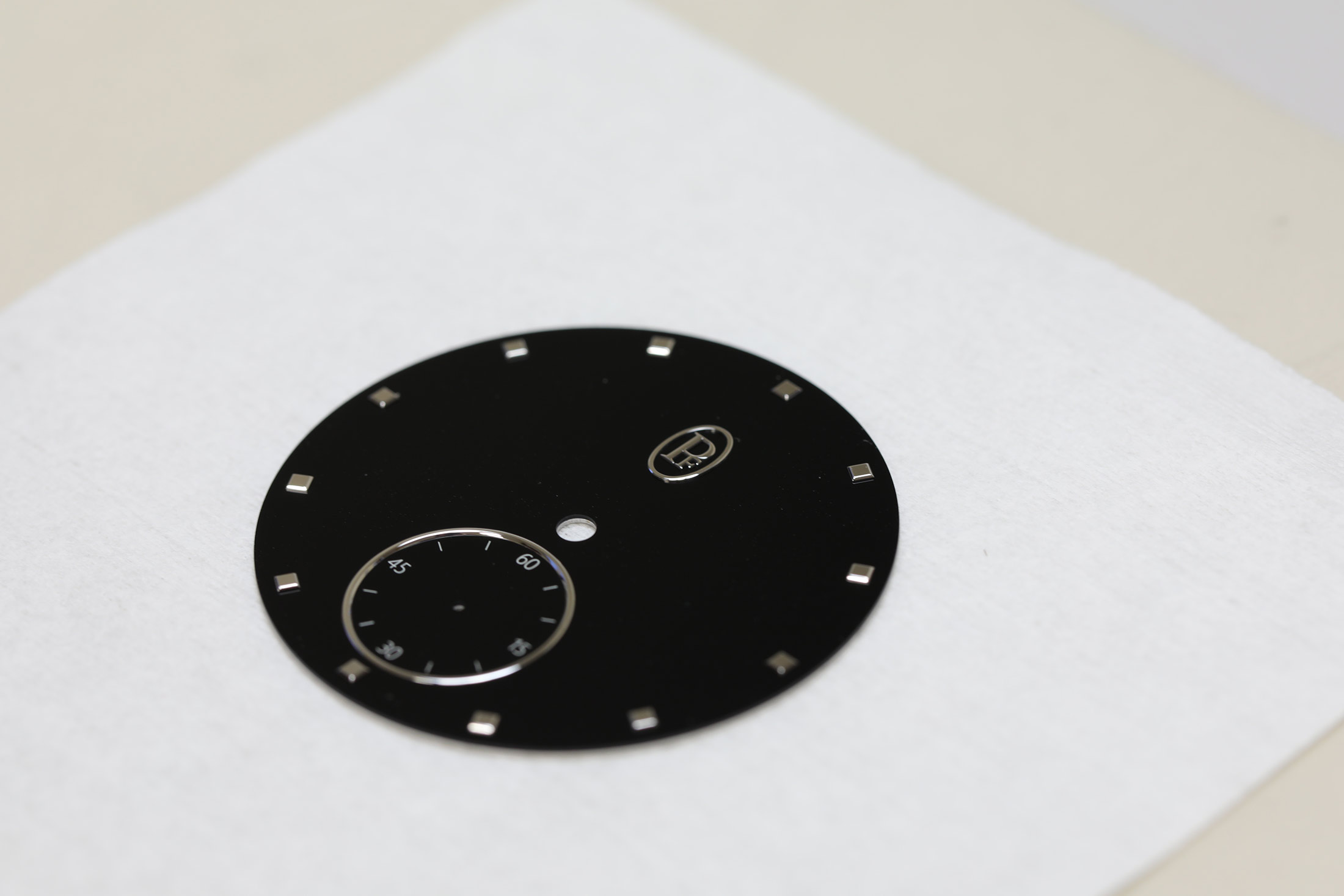

Now given the importance of Arabic numerals to the discovery of Fibonacci numbers (and to the ability to actually do useful math with irrational numbers) you might expect the dial to use Arabics but how wrong you would be. Instead, the dial is – well, not exactly featureless, but certainly a very austere thing; it's a single disk of black onyx.

There are very small amounts of white metal here and there – the "PF" logo, the indexes, the surround for the small seconds display – but other than that, you're staring into an inky, glossy abyss. This is a part of the watch where bigger is unambiguously harder as the disk, in addition to being challenging to cut at this size, has to be completely free of inclusions, any of which, if present, would stick out like a sore thumb.

The bow and chain of La Rose Carrée are both extensions of the geometric motif found elsewhere in the watch. The creation of the chain, like everything else, was handled by a specialist – Laurent Joliet, who according to Guido Terreni is the last full-time specialist maker of watch chains in Switzerland. Joliet has a boxer's forearms and the sort of fingertips you get from coaxing recalcitrant metal into shape for a living. The chain is so well-integrated into the rest of the design as to seem completely effortless and natural, but of course, actually making it was anything but easy.

Laurent Joliet

Terreni told HODINKEE an interesting story about the chain. A pocket watch chain should be an organic part of the watch, and when the watch is actually being worn it has to drape in a natural way. Michel Parmigiani's testing process for the chain was simple – he held it up over a table (I assume with something soft underneath it!) and let it fall. The chain coiled naturally as the links relaxed onto the table.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this watch – to me – is how each part of the design supports the other parts, symbolically as well as aesthetically. Take the absence of actual Arabic numerals. The Arabic – or Hindu-Arabic numerals, as they're called by historians of mathematics – that we use today were used extensively by Arab mathematicians during the Middle Ages. In particular, they made possible the work of the Arab mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, who lived during the 8th and 9th centuries AD, and who laid the groundwork for modern algebra. He's often credited by historians of mathematics, with having effected a fundamental change in mathematics – rather than treating math as fundamentally geometric, he instead made it possible for us to work with algebraic equations as abstract mathematical objects. It took several centuries for the notation he used to become more widely adopted across both the Arab and the European scholarly world but his work was a real revolution in how we understand numerical relationships.

And in the expression of numerical relationships in geometric form, in La Rose Carrée, we kind of come full circle – and I think it turns out to be truly serendipitous that Arabic numerals aren't present on the dial. They are present in spirit, though – in the physical representation of the abstract irrational number that is the Golden Ratio, and in the rectilinear and spiraling decorative motifs used for the watch.

There are few watches I've seen that cut so deep into the evolution of the basic methods of mathematics, and the techniques for calculation, that actually made horology as a science rather than a collection of ad hoc empirical practices, possible. The symbolic resonances of La Rose Carrée, and the richness of the history that it touches – Swiss horology, the birth of modern mathematics, the birth of modern science – are what made the "A" word come to mind. I still don't know that I would say this watch rises to the level of art – it's a point that could be plausibly argued on either side. But I've seldom, if ever, seen a watch where the line between art and craft was so thin as to be kind of pointless to argue. I don't know if it's art or a happy series of almost inevitable coincidences arising from the basic design subject matter – but I kind of don't care. What matters is that it's beautiful.

La Rose Carrée, unique grande et petite sonnerie, minute repeater, by Parmigiani Fleurier. Case, 18k white gold, 64mm x 20mm. Engraved, grand feu enamel covers. Not water-resistant.

Dial, solid onyx with white gold appliques including the small seconds subdial outline, indexes, and PF logo. Hands, 18k white gold, skeletonized delta shape; small seconds hand, 18k white gold, baton-shaped with square counterweight.

Movement, PF 992, original made by Louis-Elisée Piguet, number 5802, grand and small strike with minute repeater, 32-hour power reserve, running in 27 jewels at 18,800 vph.

Chain, entirely handmade, 18k white gold, with 32 links and 2 engraved squares.

Price: not currently available.

To learn more about Parmigiani Fleurier, visit their website.

Top Discussions

Introducing The Chopard L.U.C Flying T Twin Perpetual And 'Mark III' L.U.C Lunar One

Introducing The Ōtsuka Lōtec No.5 Kai

Hands-On An In-Depth Look At Vacheron Constantin's New Historiques 222 In Steel