ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Quartz technology was largely responsible for the aesthetic evolution of horology in the '70s. It created a design action/reaction from Swiss haute horlogerie giants, including Patek Philippe, who, in the face of new technology, had no choice but to get experimental. It was also the starting point of what Hodinkee alum Joe Thompson has previously called "The Fashion Watch Revolution." In the decade that followed the introduction of battery-operated watches, a vast segment of production focused less on the core timekeeping function and more on the outward appearance, evolving into fashion accessories that just so happened to tell the time.

This Japanese-imported technology spawned the rise of watch company licensing agreements by large and very well-known (capital F) fashion brands. Houses like Christian Dior, Gucci, and Yves Saint Laurent were now able to stamp their logos onto cheap quartz watch dials for mass-market dollar profit.

Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008) in his Paris studio, January 1982. Image: John Downing/Getty Images

Despite the myriad fashion brands joining the licensor/licensee cash grab, isolating Yves Saint Laurent is perhaps the most obvious choice when dissecting the modern fashion totem pole. He was a radical who threw down the gauntlet to established ways of dressing, ultimately defining women's fashion in the second half of the 20th century. The house of Saint Laurent pulled Parisian women's dress out of a staid and conservative rut in the '60s, scandalized the world with Opium (perfume), a sex-sells attitude in the 1970s, and stamped themselves bullishly across anything and everything the '80s.

Ordained by fashion empress and Costume Institute doyenne Diana Vreeland as a "living genius" and the "Pied Piper of fashion" at his Metropolitan Museum retrospective in 1983, the fashion elite have long since continued to employ the term "genius" and its worthy synonyms whenever describing Saint Laurent. This is similar to the way in which watch enthusiasts praise Gerald Genta, who we so often refer to as the genius trailblazer of horology, for changing the course of modern watch design.

Diana Vreeland and Yves Saint Laurent at the Costume Institute Gala's 'Yves Saint Laurent: 25 Years of Design' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, December 6, 1983. Image: Getty Images

Starting his career as a young apprentice to Christian Dior after the master couturier's sudden death in 1957, Saint Laurent took over the house and became Dior's successor at the age of just 21. Three years later, he established his namesake brand. What followed was a prolific output: the Mondrian dress, Le Smoking, the safari look, and the 1976 ''Ballets Russes'' show, which made the front page of The New York Times (''Yves Saint Laurent presented a fall couture collection today that will change the course of fashion''). He became the north star of haute couture from the '60s to the '80s.

Yves Saint Laurent Haute-Couture spring-summer 2002. Mondrian dress. Image: Getty Images.

Saint Laurent's ready-to-wear Rive Gauche label was founded in 1966. Where haute couture was reserved for socialites with dollars to spend and time to spare at fittings for entire made-to-measure wardrobes, Rive Gauche offered women a slightly more affordable way into the YSL dynasty, with ready-made items for sale on the younger and hipper left bank of Paris. Understanding Rive Gauche and the impetus behind its success is mandatory in understanding the business model of a company that ultimately distilled its reputation through a violently large number of licensing agreements. It was the pathway to expanding the YSL empire.

Pierre Bergé, partner, co-founder, and later president, had spent the '60s and '70s constructing an image out of the Yves Saint Laurent brand. Bergé was ahead of his time in persuading customers to buy into the lifestyle that YSL represented. Given the intrigue behind the scenes of the ruling Paris fashion houses, he built a story around Saint Laurent, the couturier, turning him into an alluringly potent incarnation of the brand. Saint Laurent was even in his own advertising campaign, famously appearing naked for the launch of his YSL Pour Homme men's perfume.

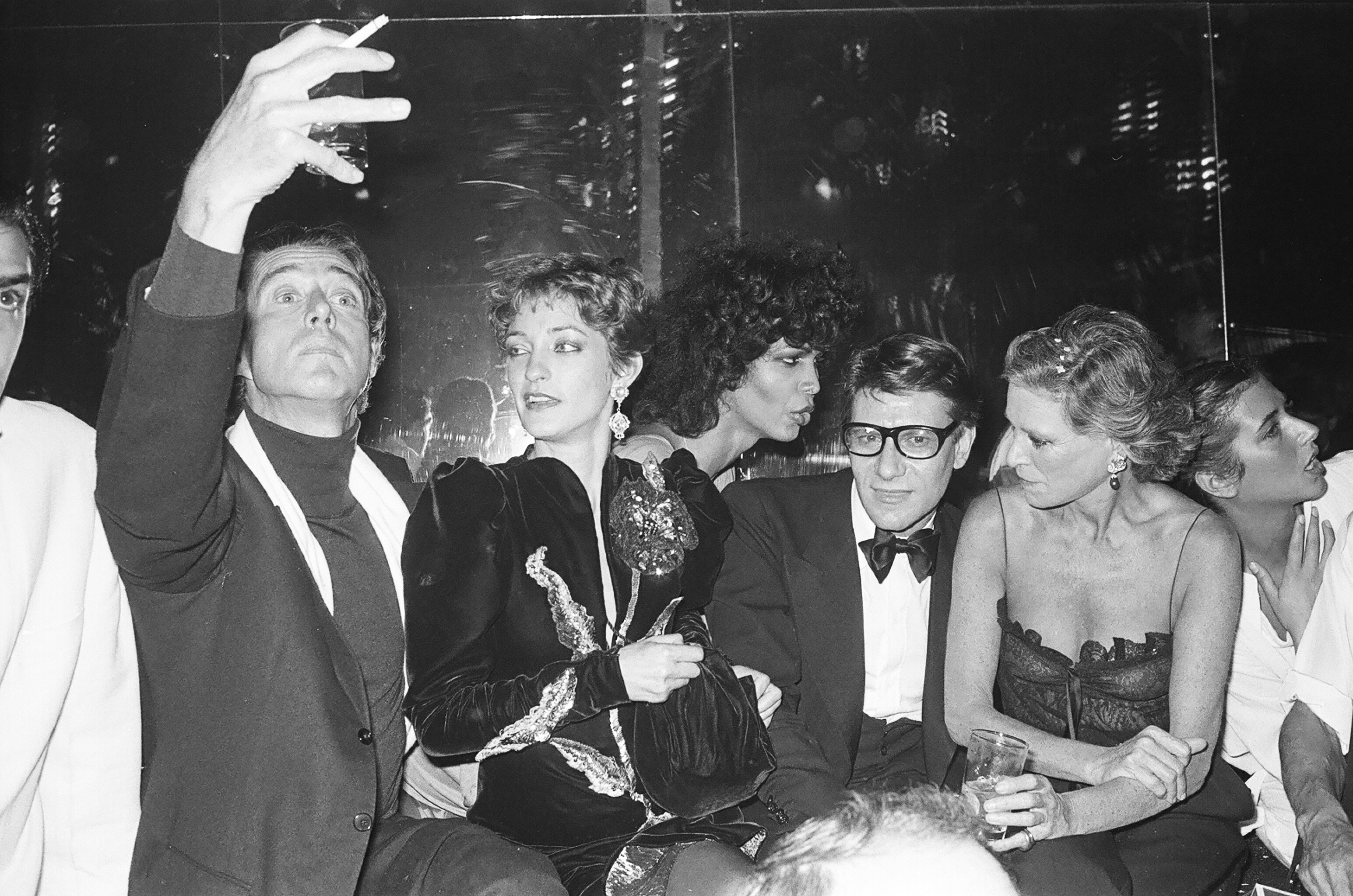

Halston, Loulou de la Falaise, Potassa, Yves St Laurent, and Nan Kempner at the Opium party at Studio 54 on September 20, 1978, in New York City. Image: Getty

Cosmetics and fragrance were but a precursor to an even more expansive host of global licensing agreements. In 1975, Citizen started manufacturing and releasing YSL (Yves Saint Laurent) licensed watches exclusively for the Japanese market. YSL handled the design, while Citizen handled the manufacturing of the products. The initial product line was created based on the demand for authentic dress watches that were two-handed, manual-winding, and slim in design. The early designs were created loosely in line with YSL's elegant aesthetic code. The outcome of the collaboration was a range of smartly designed, well-made gold-plated quartz (among a few mechanical) watches.

YSL x Citizen quartz. Production circa '80s. Image: Courtesy of Beverlyna Indonesia

Slim and sleek with a palette of rich browns and purples or simple and clean black, the watches were designed with precisely deployed lines that framed an experimental use of textures (snakeskin!) and colors. It was the 1970s, which meant a tale of "anything goes" in watch design, but these earlier Citizen YSL models were smooth, subtle, and sophisticated. The fashion imprint left on the timepieces was charming, not overbearing.

Today, Citizen might not incite a feverish picture of glamour and opulence, but the early Citizen YSL collaborations were well-designed and fairly good quality. During the mid-'70s all Japanese watch firms adopted quartz technology, playing their hand at bridging the ideas of affordability and luxury. The undisputed leader was Seiko, but Cross-Tokyo rival Citizen (albeit much smaller in those days, with revenues amounting to roughly one-quarter of Seiko's) was also at the forefront of the quartz aesthetic revolution. It was a period of great experimentation, there was no one right aesthetic answer given that it was relatively cheaper to create watches.

Vintage Citizen employee catalog. Image: courtesy of Citizen

There was at least a degree of calculated aesthetic crossover with the YSL universe during the collaboration's inception and earlier years. The watches were sleek and sexy and aligned nicely with the seductive hedonism of the 1970s (Opium scented) Saint Laurent universe – a little affordable slice of YSL rather than the whole Yves Saint Laurent couture pie.

A 1970s mechanical YSL "Reverso" Image: courtesy of C4C Vintage Watch Store.

Mechanical and quartz "Reversos" Image: courtesy of a Portuguese watch collector

So why would a globally revered Parisian maison like YSL, whose world was composed of haute couture, glamour, and French it-girls like Catherine Deneuve, want to attach its name to a licensing agreement selling lower-tier, mass-market timepieces? Bergé was cynically successful in promoting the company – as president, he ran not just a fashion house but a global mass market company capitalizing on the power of the YSL logo. A logo that had selling power long before logo mania in the '80s and '90s. A vertical italicized monogram so impactful that before the FIFA World Cup Final in 1998 (which was viewed by 1.7 billion international spectators on live television.) Yves Saint Laurent staged a huge fashion show at the Stade de France, featuring 300 hundred models who formed a giant YSL logo on the pitch.

The logo eventually came to bear a tinge of despair, a relic of faded glory even. Violent volumes of licensing agreements – Saint Laurent signed his name to everything from sunglasses to bed linens to cigarettes – began to exhaust a brand image that was so strongly evocative of Frenchness. In 1997, Citizen Watch Co. of America was licensed to develop and market a collection of Yves Saint Laurent watches to be distributed in the U.S. and Canada. The YSL license was actually granted to Citizen by Cartier, the worldwide master licensee for YSL accessories, including watches, jewelry, leather goods, and pens.

Citizen x YSL from the '90s.

Along with a rise in the flow of licensed products from higher-priced brand categories, there was a growing preference for well-known brands from consumers in department stores and retail outlets. This created the perfect environment whereby very desirable, well-known labels from other product categories (license brands) could enter alongside watch manufacturers' proprietary brands. During this period, product development for YSL watches was led by the U.S. team and developed with the approval of YSL France, but the product lineup was positioned exclusively for the North American market. The collection made its debut at fine jewelry and watch trade shows in Geneva and Basel in April of 1997. Aimed at department stores and fine jewelers, The concept was "Sporty Elegance." The lineup primarily focused on pair watches, with a price range between $150 and $500.

Carla Bruni (L) and Karen Mulder (R) with Yves Saint Laurent after the Saint Laurent during his Haute Couture Spring/Summer 1996 show. Image: Getty

These watches were, at best, a mere dilution of the once dynamic and disruptive Yves Saint Laurent look. It was an inevitable consequence for a brand that stamped itself imperiously across anything and everything product-wise in the '80s and '90s. YSL sold the ready-to-wear business to Gucci for some $1 billion in 1999 and shut down the couture house when Saint Laurent retired in 2002.

Gucci's Tom Ford, taking charge at Yves Saint Laurent, terminated and cleaned up the licenses on which France's renowned fashion house was built, "Stamping your name on fashion products used to be a license to make money. Now, a smart designer looks for a license to kill," announced Suzy Menkes in The New York Times in July 2000, "The theory is to create a leaner, fitter luxury world in which clients are better served and designers reap the benefits of bigger profit margins for their own stores."

A genuine aesthetic revolt is hard to come by. And by revolt, I mean a large-scale, era-defining, old silhouette-revoking, new silhouette-imposing, sartorial global infiltration. During the latter half of the 20th century, Yves Saint Laurent led a fashion mutiny and conquered victoriously, creating one of fashion's most revered houses and virtually inventing ready-to-wear with Rive Gauche. Fashion watches followed the same revolutionary path, albeit far less glamorously. Foresight and technology in Japan turned the horological status quo on its head.

Today, licensed watches are relegated to the confines of mid-tier luxury, along with perfume and sunglasses. In 2024, "Fashion Watches" have been redefined with the big maisons (Dior, Hermes, Chanel, Louis Vuitton, etc) now pursuing their own mechanical watchmaking facilities or developing partnerships with well-known Swiss suppliers. But perhaps we could argue that without the quartz revolution and early licensing like YSL and Citizen, that Louis Vuitton may not be making Tambours nor Chanel making J12s?

Top Discussions

Introducing The Chopard L.U.C Flying T Twin Perpetual And 'Mark III' L.U.C Lunar One

Introducing The Ōtsuka Lōtec No.5 Kai

Hands-On An In-Depth Look At Vacheron Constantin's New Historiques 222 In Steel